Over the summer of 2020, I, along with 9 other printer/designers, created a limited edition Field Notes notebook. In the midst of a global pandemic and viscerally witnessing and feeling the loss around me, in life and life’s work, I wanted my design to be a tiny nod to the spaces that make a community home. A safe community. A connected community.

These are some candid shots of the building and printing process. See the wonderful short doc Field Notes did on the entire series. Some notebooks are available for purchase in the shop. Please continue to support these independent makers and all of the ones in your community.

The City Is My Religion — Requiem

I wrote a requiem when I turned 40. It was for a part of myself that bore a nagging, persistent allowance of words that diminished me and the work of my hands, words that always came from men. I could wax on about why they did this but tomes have been written on the subject already; I could address why I tolerated it but this is also well-covered ground.

The only pseudo-apology I’ve received from a man was ‘sorry, I thought you were a boy.’ I think of this whenever I’m put in a position with a man who wants me to demur to his authority or knowledge so that I’m forced to pause before the words ‘sorry’ or ‘apologize’ escape from me. Because more often than not, it’s a power play and my knowledge is just as powerful.

I constantly correct my child on apologizing: If I say ‘do your laundry’ then do your laundry; it doesn’t require an apology for not having done it. It requires saying ‘okay’ and doing it. No offense has been committed. I’m not sending a child into the world apologizing for their very existence.

I see criticisms of women’s work on social media and the woman posting is quick to apologize for whatever the commenter deemed insufficient. I message her to say ‘Don’t apologize for the work you put in the world!’ More often than not, the troll has nothing in their own feed to indicate they have any advanced knowledge of the subject and if they were truly invested in helping, they’d do it directly and privately and not in a humiliating fashion. It’s a power play.

I’ve tried, whenever possible, to collaborate with other women in my field and have had deeply satisfying results on personal and professional levels. Sometimes a friendship goes years in search of a project and other times I cold call a woman I admire to see if there’s a collaboration waiting to happen.

In 2016, I worked with Jessie Reich of Three Ton Bridge Type Foundry, operating out of the Bixler Letterfoundry in Upstate NY, to create two Chicago Collections of metal ornaments based on architectural elements in the city. You can read more about this project here.

And in 2017 I had the pleasure of collaborating with Geri McCormick of Virgin Wood Type, also in NY, to create two sets of wood type ornaments drawn from looser, prairie-style ornament. Read about developing Ida and Lucy here.

Clearly a print in my typographic memoir needed to cover the fact that I was a woman in print, that I worked in letterpress at a time when it was gaining greatly in popularity and transitioning from a male dominated field to a female one. So I collected many of the things men said to me over the years and wrote them down. Some were actually sent in letters and postcards and I kept them but don’t want to give the senders any more space here than they deserve.

It felt important to use all type designed by women for this print. But therein lies the conundrum– there isn’t much, or at least it isn’t specifically documented and credited to women. So I started with my own ornaments mentioned above, arranged in quilt-like patterns as a nod to a traditionally female craft.

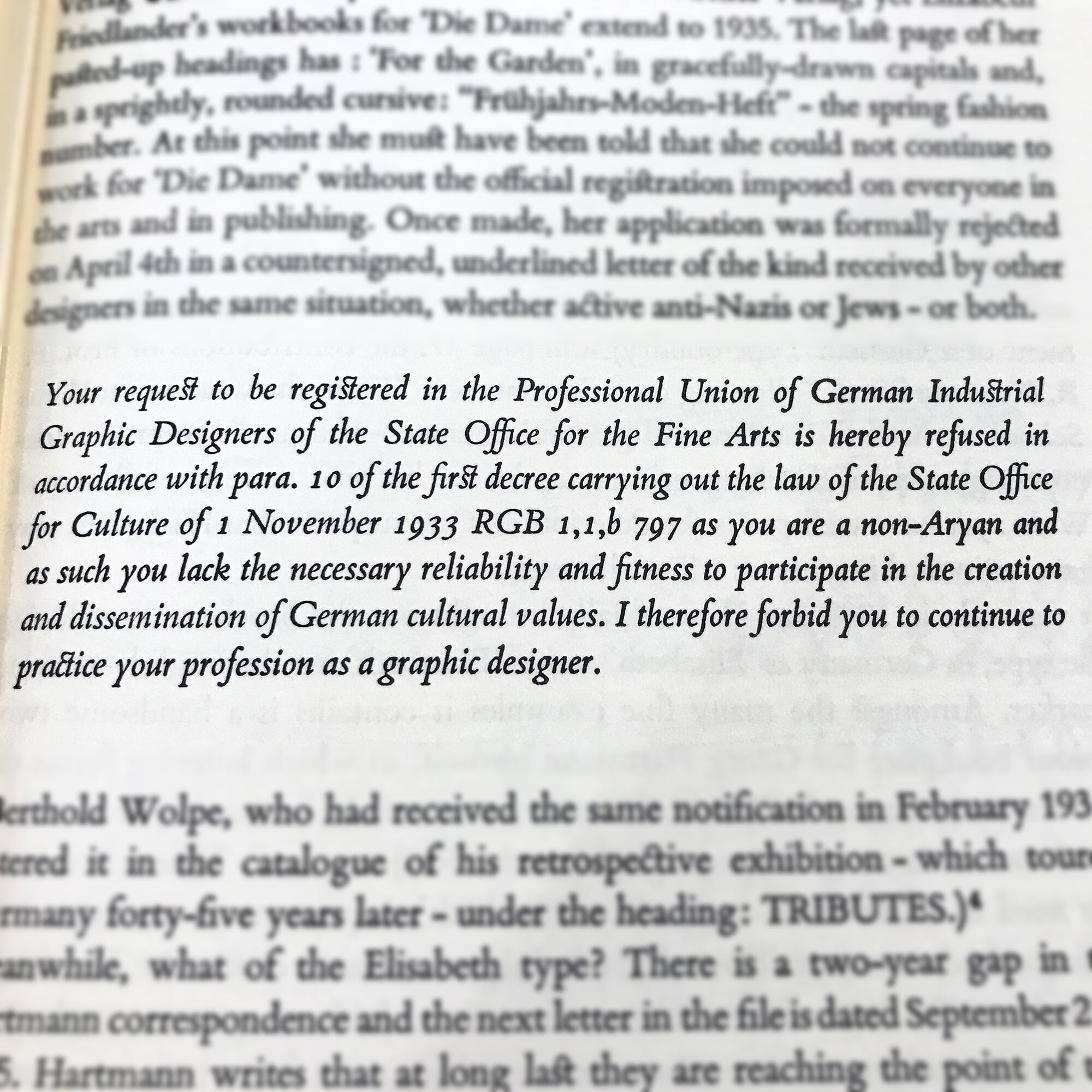

In the winter of 2017 I had the wonderful opportunity to meet Caryl Seidenberg in her home north of Chicago. Moving away from making books, she was selling most of her collection, including a nearly complete run of the typeface Elizabeth, designed by Elizabeth Friedlander. After a delightful morning of looking at her past projects and gleaning what I could from someone who also balanced work and motherhood, I left with all of the Elizabeth type. The Newberry Library has a small archive of materials about Friedlander, including Pauline Paucher’s wonderful book about her life and work. A Jew working in Germany in the late 30s, she was forced to flee to Italy and then England, where she continued to live and work following the war. It’s a story worth reading if you can, even if it requires digging and visiting your special collections library.

I think of the phrase ‘I forbid you to continue to practice your profession’ whenever I’m confronted with sexism because any ‘ism’ is based on the supposition that a perceived flaw prevents one from effectively producing or being something, that your ‘otherness’ is a disability. And after I think about it for a minute, I figure out how to do whatever it was I was told I couldn’t do in a more thoughtful and engaging way to show that I could do it. And this is why anyone marked out as ‘other’ from the ‘norm’ should be listened to; this extra hurdle is where the very seed of innovation is planted.

On May 7th, 2017, my neighbor called me to come home immediately as my house was on fire. By the time I arrived, there were firefighters on the roof, punching holes in it to allow for the release of smoke as the fire itself was out. The rest of the evening was a blur of insurance calls, board ups, neighbors checking in, consoling my child (the electrical fire started in their room and it was a near total loss) and coping with the shock. This image encapsulates so much of that; it shows the layers of my 100 year old home exposed in a near instant.

My little house is a huge source of pride for me. We purchased it in a perfect storm of dumb luck that I never thought would happen: the height of the recession with drastically falling home prices, my husband had steady and rising income from working one job as opposed to several (rare for a stagehand) and Obama’s $8000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers. I had my heart set on one of Chicago’s historic tiny brick bungalows and we got it.

Chicago is well known for its 1871 Great Fire. It took the city about 3 years to rebuild from those damages. It took 9 months to rebuild our home, an excruciating process of constantly calling contractors and cleaning and fighting with utilities and hand-wringing, all while attempting to make life feel normal for a child and running a business. And at the end of May, I dragged my tank of a sewing machine, still reeking of smoke, to Jo’s school to make costumes for the school play. It wasn’t until a while later that Jo realized the irony of being cast as Mrs. O’Leary in a play about Chicago’s history.

And so I built a print to memorialize this time much the way the city was rebuilt on top of sedimentary layers, only my layers were of type dating back to the fire, with my little house resting on top. Then they were printed in earthen, ashen shades.

To add flames, I created a 3-color reduction linoleum cut, printing, then carving away at it multiple times to print depth.

The final print:

I wish I could say the fire experience came with growth, that renovation gave my walls a satisfying symmetry, that I’m relieved our electrical work is up to code. But I can’t. It left a constant, quiet dread, knowing that one day you can leave your home and come back to find it on fire and that you have no control over this. That your definition of ‘home’ and ‘safe’ can vary greatly from your friends and community. That losing a home is like losing a loved one and when someone says ‘but look, you can get a new renovation!’ it’s akin to ‘look, you can get a new child/mother/husband!’ when they die. It wasn’t until the Paradise, California fires when I heard a therapist working with families there express this loss in a way that made me feel understood. That grieving and fear is appropriate. That it’s normal to look at your child when you’re both leaving together and the house is alone by itself, with an unspoken understanding of these feelings.

When our renovation was taking place, its very nature of removing the damage meant removing nearly every bit of handiwork my late husband put into the house and it was like losing him a second time. I was lucky to find a few ‘easter eggs’ in the rubble, including this piece he buried behind drywall in the attic.

These little artifacts are important because they are finite, having lost Mr. S in 2016. He was fiery and passionate about many things, but they largely boiled down to two: his love of his job as a union stagehand coupled with the respect he had for his fellow workers, and his deeply held belief that everyone deserved equality and a start on a level playing field. That meant that if he wasn’t enjoying a cheap beer in our yard, he was at the theater or at a protest rally for whatever underdog needed a loud voice (and he had one). At one of the Newberry Library’s Bughouse Square debates, I watched him heckle Quentin Young while he spoke about the problems of the AMA and the need for single payer health care, something Mr. S actually believed in. Afterwards, he approached Young to shake his hand and say, ‘I believe in everything you said, but I think it’s important to have a lively debate’ and they laughed. If that’s not Chicago, I don’t know what is.

I focused the print about his life on the last few months of it because it was in this time that Mr. S’s long-held beliefs in the strengths and benefits of unions (not always a popular opinion) paid dividends. Over the nine months of his illness, the union showed up in every possible way to support us, thereby validating his lifelong struggle to defend them. Even in the hospital, coming out of anesthesia, he discovered his nurses weren’t in a union and he offered to start one on their behalf.

So I stuck to all the simple, sans serif typefaces, not unlike what we’d see at so many rallies and marches, and organized them into what could either be a sea of posters or the curve of a theatrical proscenium arch. The center pulls specifically from Billy Bragg’s ‘There is Power in a Union.’

Overlapping ornaments point the eye upward, doubling as footlights or poles for the posters.

The shapes of the blocks of text were printed with rough linoleum blocks and then hand inked for a little dimension with this down-and-dirty frisket.

Before Broadway went dark in March, we saw a production of Hadestown, a stunning, modern telling of Orpheus & Eurydice. While we know this is tragedy and long for a different outcome, Hermes is there to emphatically remind us ‘it’s an old tale… it’s a sad song… but we’re going to sing it again.’ The cast follows the performance with an ask for donations to Broadway Cares, an organization founded to help those in the industry fight HIV/AIDS when the rest of the country chose to ignore it, and has grown to help the entire Broadway family when in need. They helped my family in our hour of need. As we left the theater and dropped money in the red bucket, I thought ‘what widow placed money in this bucket five years ago that helped me and my child?’ Hermes was right.

I didn’t write this particular requiem and I can’t change the lyrics. But I, too, will sing it again and again.

This is the second of four posts about The City is my Religion.

Read the first here.

Consecrated Ground

Death and the act of dying are such a huge component of living that it always surprises me when people deny it, refuse to discuss it or fear the fact that it will, indeed, happen to all of us. If anyone could write about death as a companion to life in all of its true and metaphorical senses, it was Charles Dickens. And of his novels, Bleak House remains my favorite. Death comes to its characters from all classes of life, from sources as simple as bad genes to the inequities of a ridiculous legal system.

Early on in the novel, the death and subsequent burial of a character known as Nemo (Latin for ‘no one’) is rendered poetically in a paragraph that describes this final act while, at the same time, pointing out we’re classless in death. It is only later, as the novel traipses on, that we see how this character was the artery tying together all of the remaining characters, from all stations in life. And so I chose this as the text for a new print, with the intention of alluding to the graveyard mentioned.

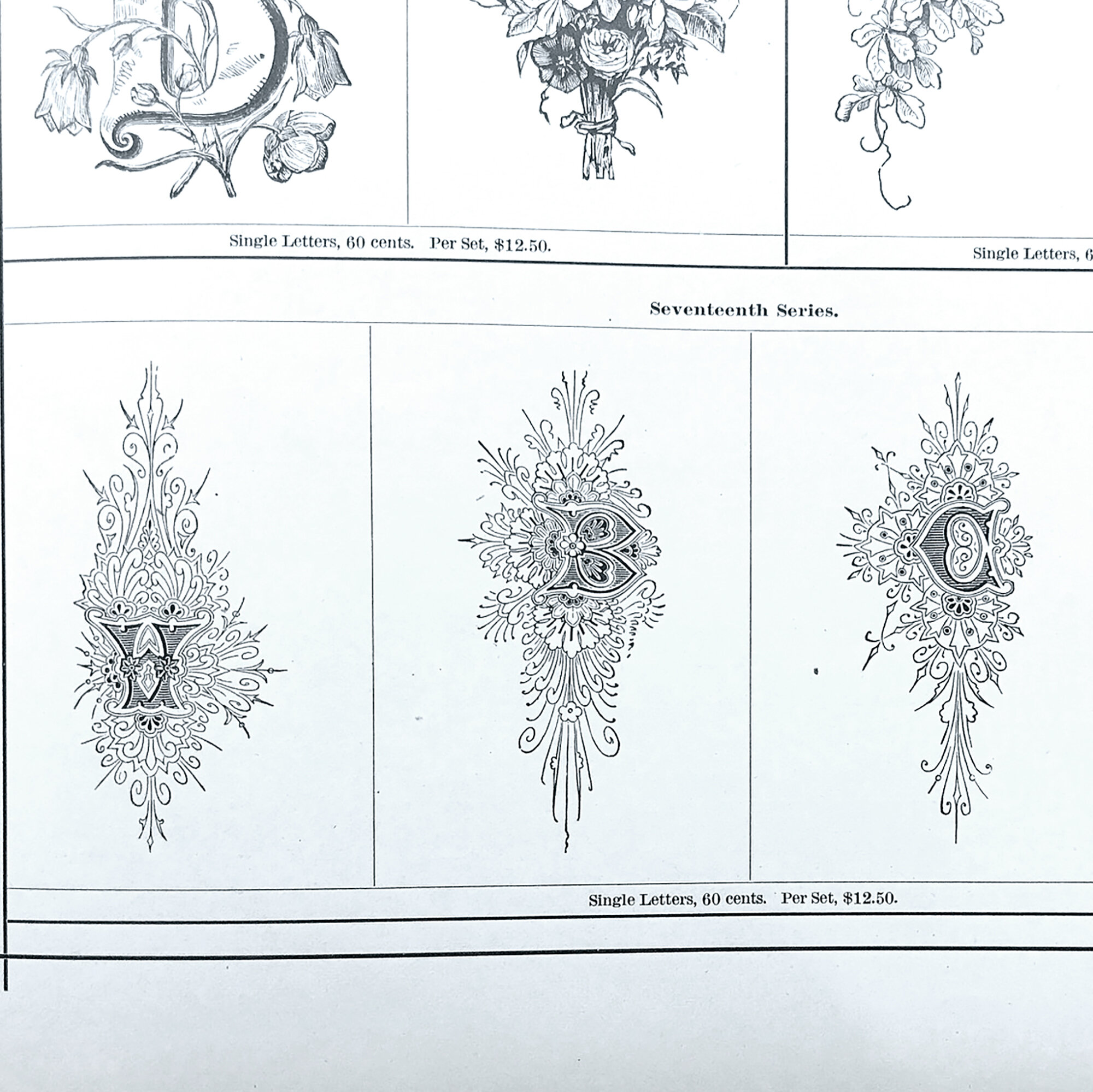

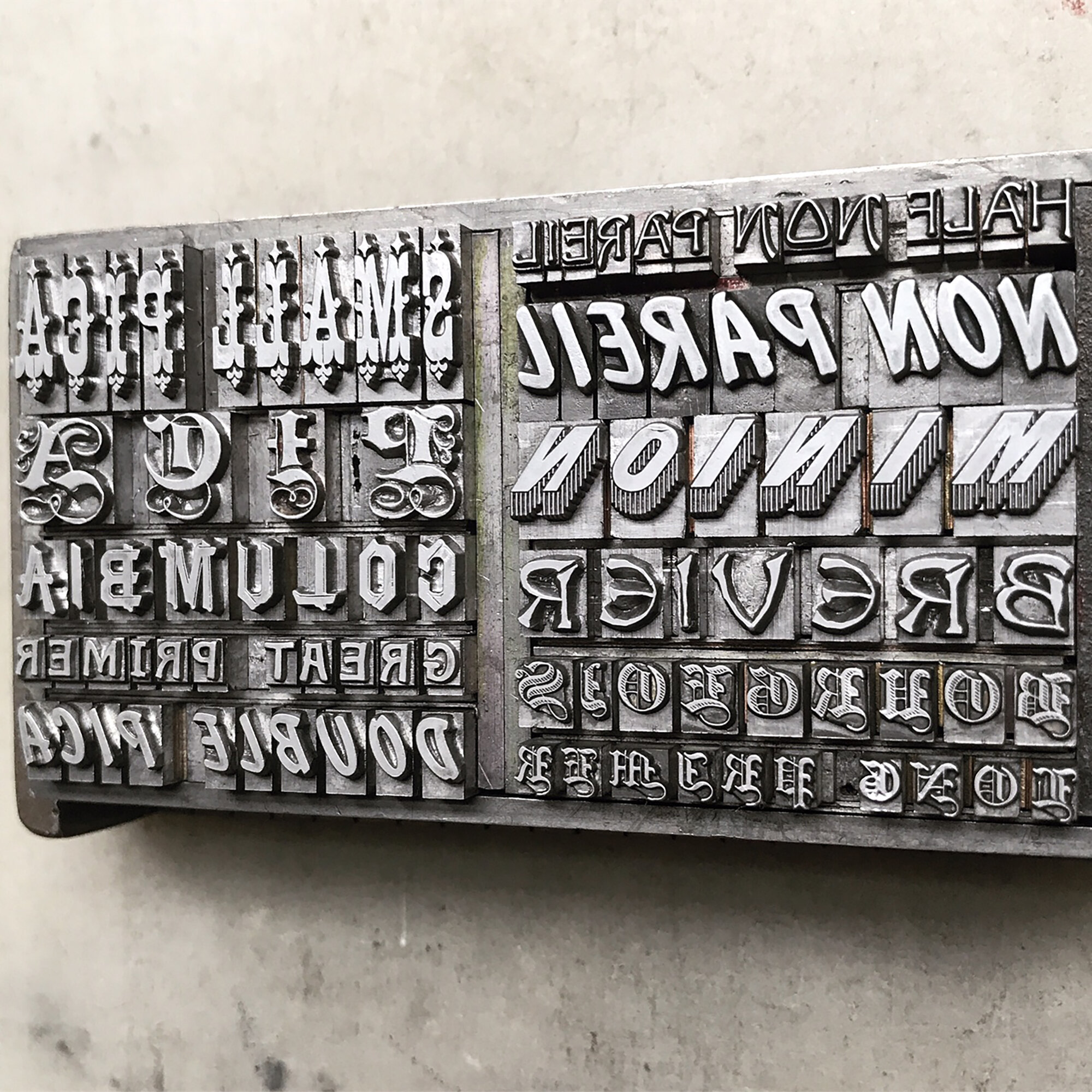

It felt appropriate to dig into my 19th century type collection, some extant of that period with others cast in recent decades from historic matrices. The ornaments needed to have a stately feel that matched the type but also could have been carved on the headstones.

Many of the ornaments used are the most beautiful in my shop in terms of their detail and complexity. The art of typecasting was definitely at its height in the late Victorian period in this respect. These collections come largely from Barnhart Brothers & Spindler and MacKellar, Smiths & Jordan.

Nemo’s death in the novel casts a long shadow and sparks a series of events that lead to revelations and… you guessed it, more death. When another character hears of his passing after not knowing he had even been alive so recently, she asks at his burial site, in a lamenting tone, ‘Is this consecrated ground?’ It’s clear this knowledge would bring peace more to her than the deceased. I set this text in wood type to resemble a shadow stemming from the gravestones.

To give structure to the gravestones, I carved a simple linoleum cut after tracing the shapes from the final print. I almost always print largely transparent color blocks after the darker type, knowing it won’t compete with the black ink. And the type, had it been printed over the transparent base, won’t pool on top of it at different rates given the various opacities of ink. Given the texture of the paper, I wanted the linoleum to print darker at the base of the gravestones and fade upward, both to allow the type to pop more and to tie the base of the stones to the shadow text.

Below is the final type form, followed by detailed shots of each grouping. I try to allow 19th century type to guide me, given that it was designed to create intricate forms.

The final print is on Fabriano Tiziano Charcoal-colored paper to set the mood. The inconsistencies in the linoleum along with the subtle variation in ink tone created exactly the aged-stone look I was hoping for.

‘Together’ is the only decidedly 21st century type, having been designed by Russell Maret and cast in 2016. But it fit the tone and is a stately end to the excerpt.

The print is now available here in a limited edition of 40 copies. 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of Dickens’ death and having a moment, in print, to honor this while contemplating those lost over the past few years is the perfect cap on the last decade.

The City Is My Religion — Invocation

On June 28th, 2016, I sped through the suburbs from the hospice where my husband would soon meet death. I’ve no memory of the exact location, only that it was in the vast all-cars-no-sidewalks suburban terrain I can’t stomach. Politely manicured lawns and strip malls on both sides, with no signs of live humans. I sobbed because my city-loving husband had to die there.

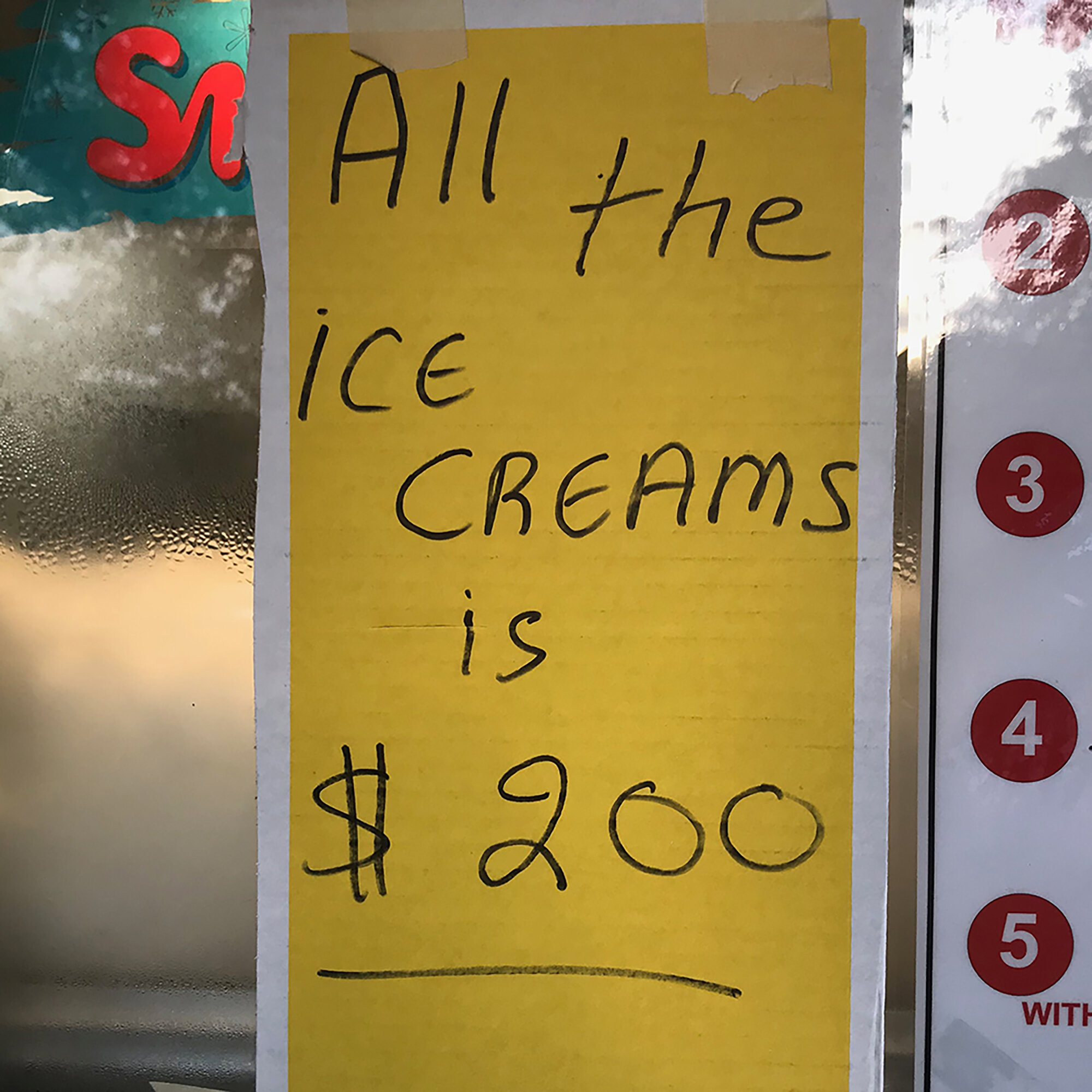

Maneuvering back into Chicago, I drove down Kedzie Avenue and immediately stopped at an intersection to allow a woman to cross while pulling a child’s wagon. It had a precariously balanced dresser sitting on top, with its normal occupant in the street behind it, pushing energetically as his mother heaved it through the crosswalk. I chuckled at this scene from my neighborhood. I was back where my environment glowed and all the ice creams is $200.

In the midst of end-of-life discussions involving religion to which I did not subscribe, I realized the city fulfilled that role for me. Pacing the streets, seeing my people at the shops and carrying on in an immediate, embracing environment provided the solace that many, I suppose, get from a religious life. Circumstance told me a page must be flipped to a new life chapter I wasn’t ready to read. Could I look to my first 20 years in Chicago, examine their foundational structure, then create a memoir in print to both honor the past and provide a scaffold for the future? The work of my hands is and always has been, free therapy.

I applied for and was granted the Arthur & Lila Weinberg Fellowship at the Newberry Library, for research to develop my idea of what this project could be. The steady rhythm of searching titles, laying out one’s pencils and notes, receiving beautiful objects on little cloth futons, then getting lost for hours in what is, for the bibliophile, consecrated ground, was both a balm and a directive.

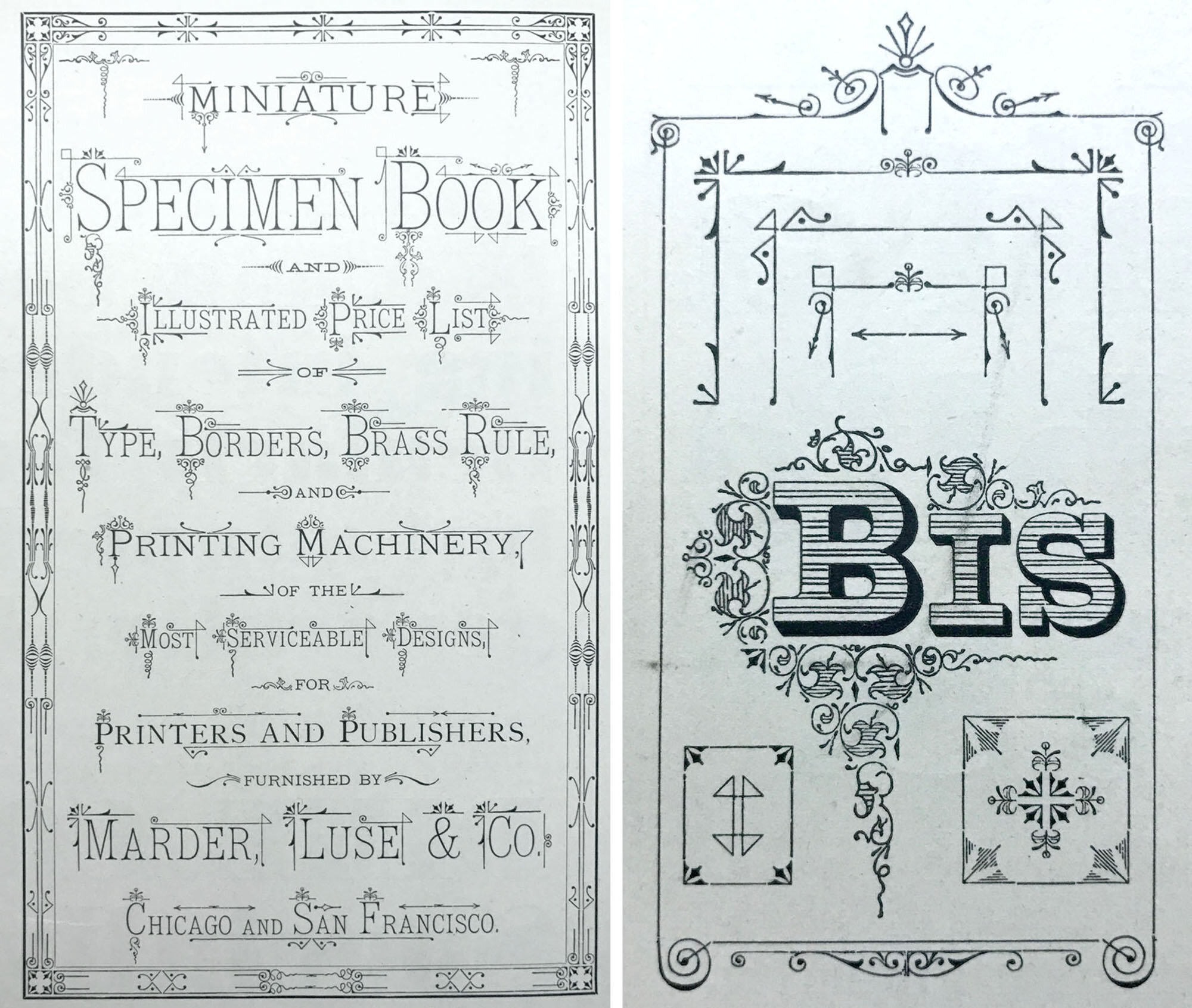

I examined the definition of a type specimen book to explore if it could function as a memoir as opposed to its more traditional role either documenting type for sale or satisfying the vanity of a printer. Because I am not a foundry or reseller of type, and because my collection is anything but stagnant, a specimen could be freed to take on the life I choose to give it. As Russell Maret recently wrote, “In the absence of new types, then, a specimen book that fails to present old types in new ways brings its own existence into question. Why bother?” I couldn’t agree more.

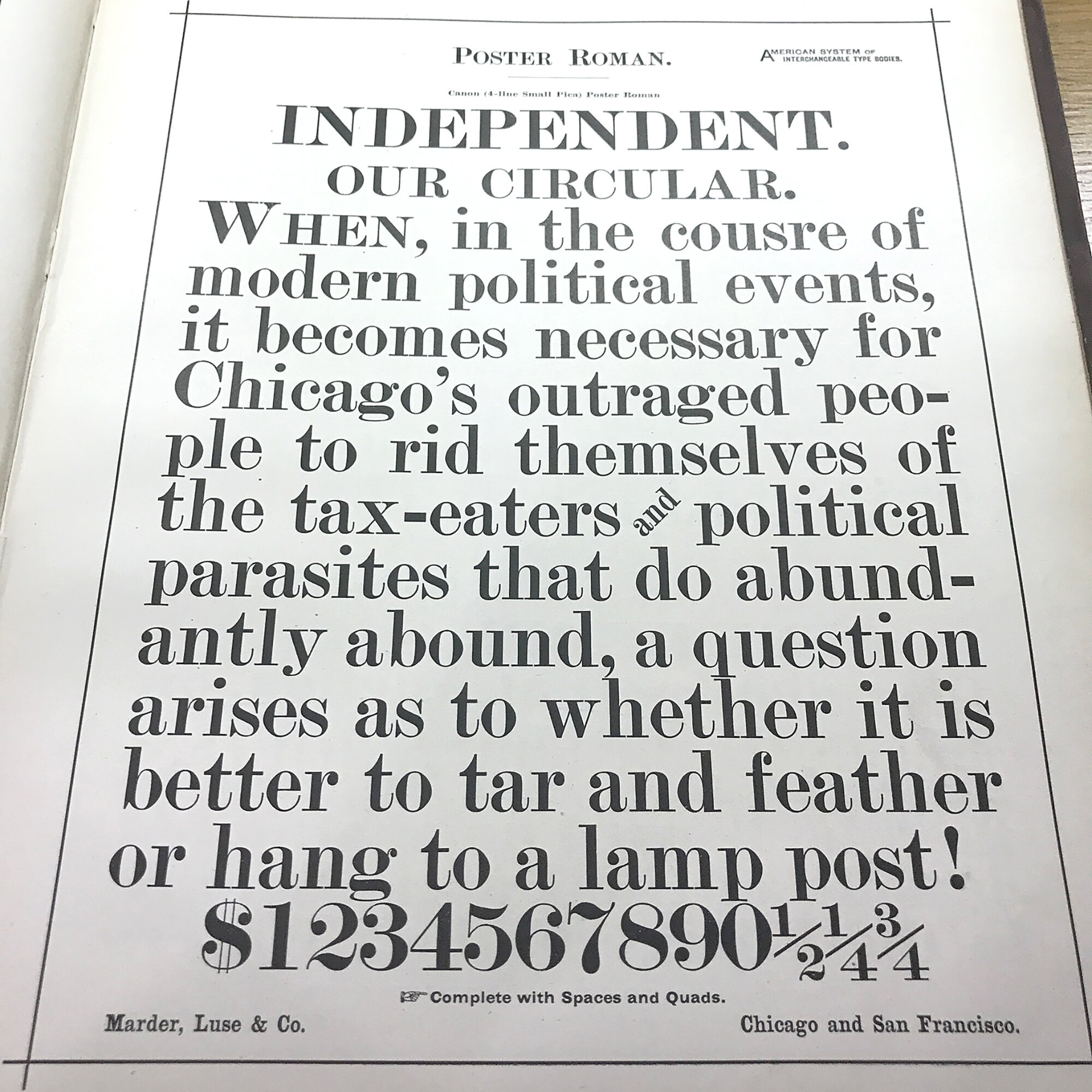

While perusing 100 year old specimens in the Library, I particularly enjoyed finding typos and mistakes as a reminder that a human hand built the form.

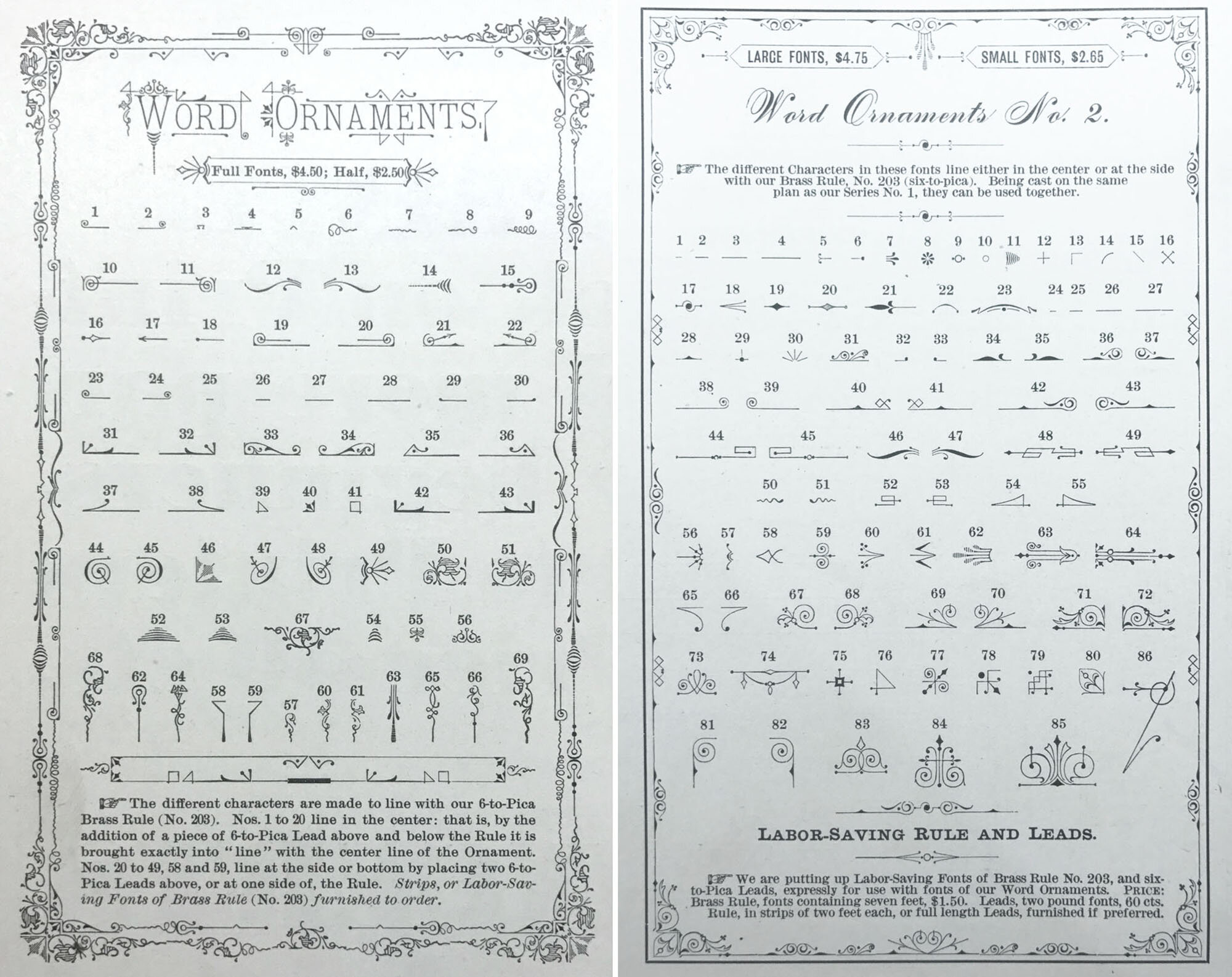

Of particular interest were these word ornaments from the Marder, Luse & Co. books, a Chicago-based foundry prior to 1900. This is because I own many of these sets but wasn’t sure how they were designed to work together.

Studying these helped flesh out what would be the first of 10 themed prints, this one focused on the definition of perseverance.

The text for the print was pulled from diverse definitions of the word, from the dictionary itself to Curtis Mayfield and Sesame Street. The largest within it is my own; it is a nod to early morning sightings of bread trucks all over the city. This singular vision reminds me life is going on and that whatever happens that day, I can always get a hot dog at the end of it.

All of the typefaces used for this print are generally hated by both type enthusiasts and casual armchair designers. Let’s hear it for Murray Hill and Park Avenue! How ya doing, Brush Script and Typewriter? Never enough of you, Cheltenham, old friend. Groan all you want, few typefaces have persevered liked these champs.

With this print, I established the three design tenets each subsequent print would follow:

Typefaces grouped by theme of my choosing

Historical component connecting print to specimen books, printing, etc.

Personal story, reflection, connection to the city of Chicago

The second print would ultimately become the cornerstone of the project as I compiled the tools to build a church. But this would be a monument to the places that shaped me into a Chicagoan and set me on a path to collecting a ridiculous amount of metal ornaments, many of which were designed, cast and used in Chicago for decades prior to my tenure as owner.

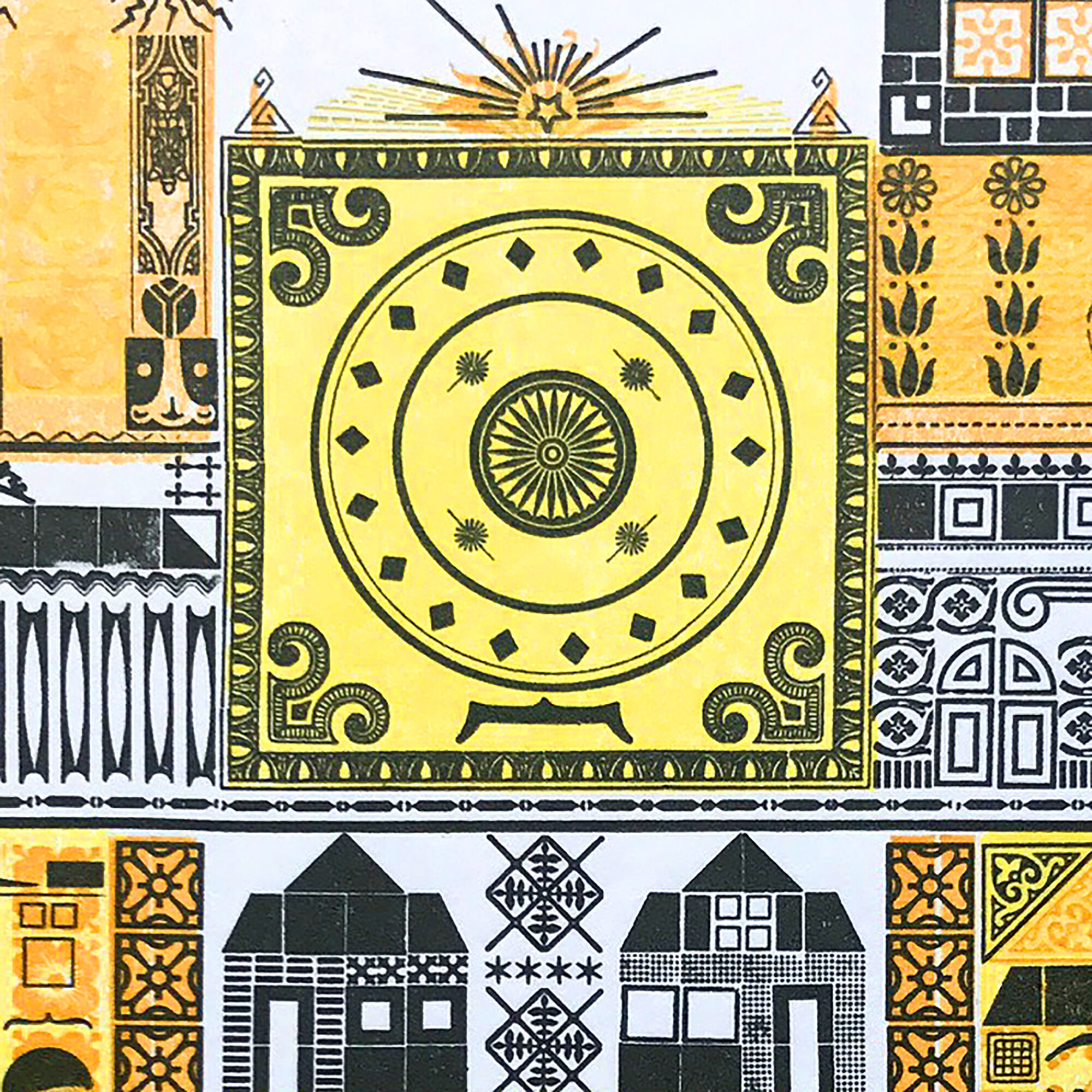

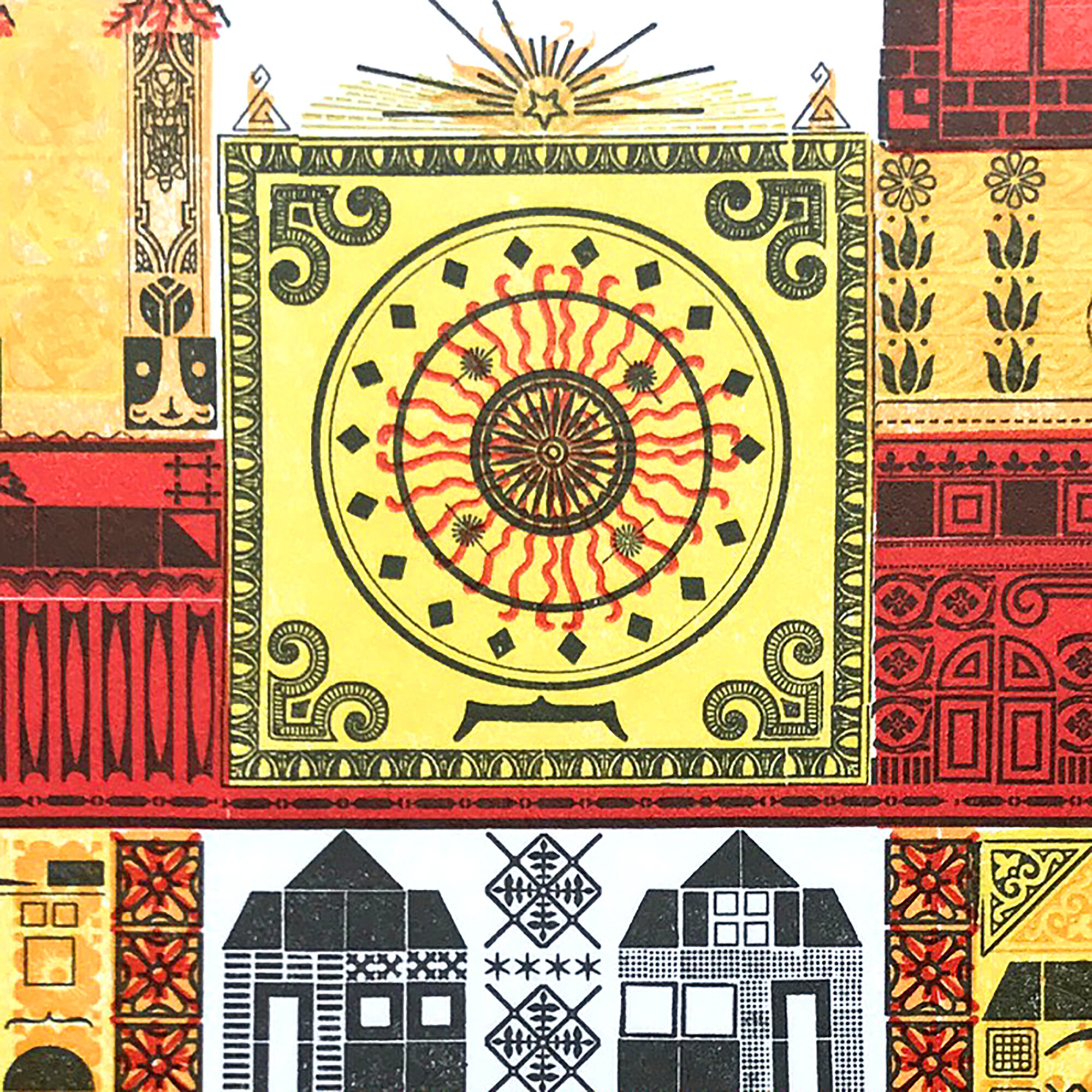

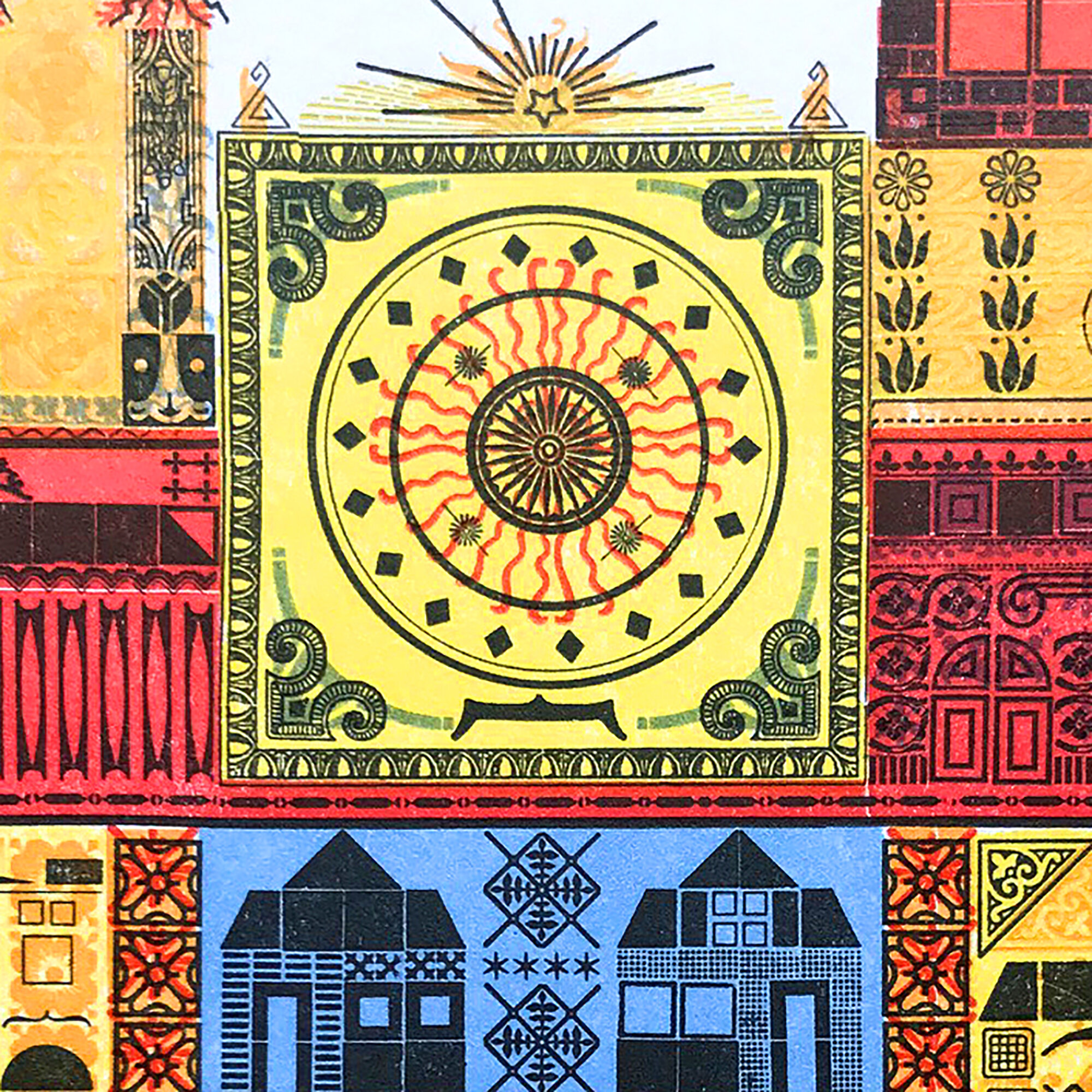

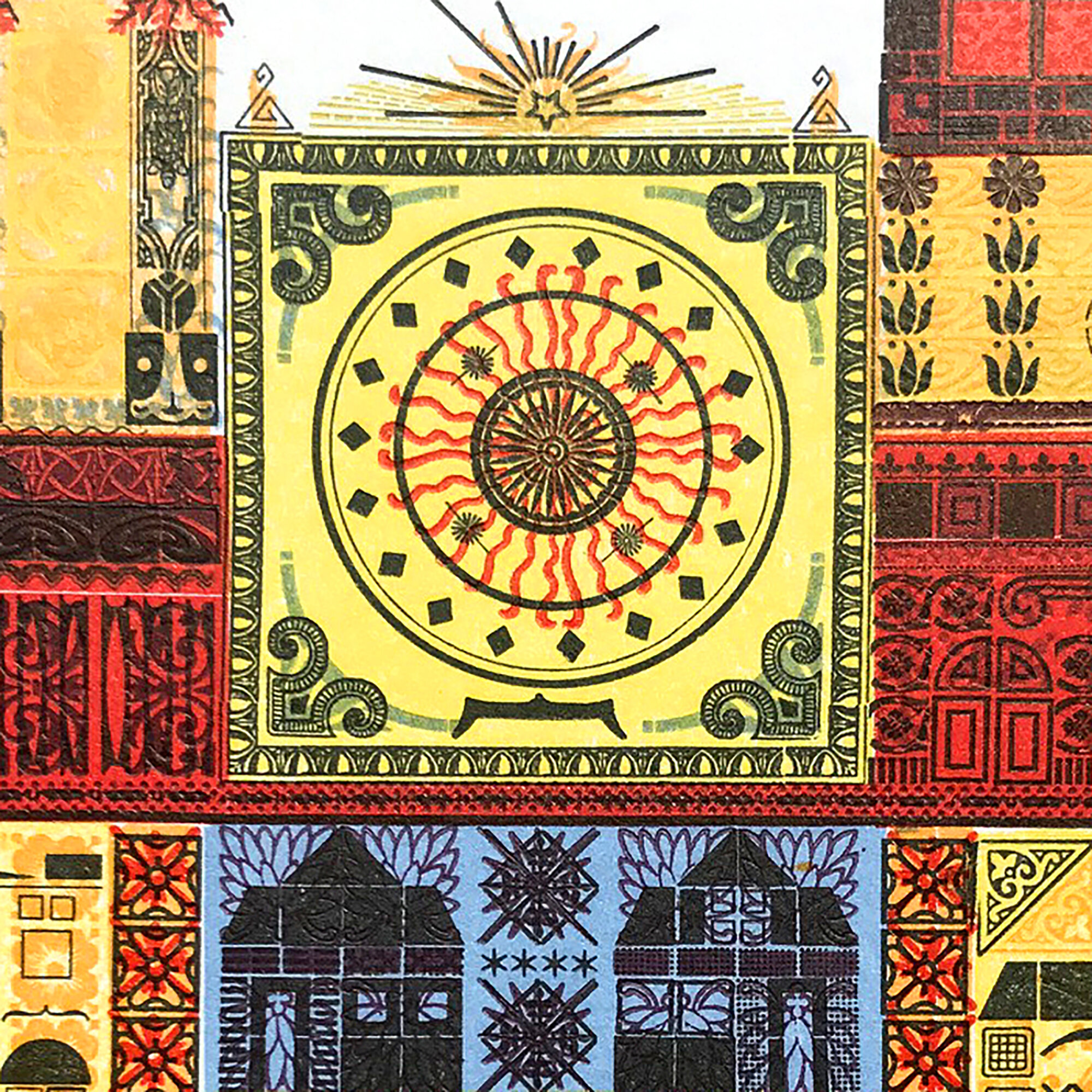

While at the Newberry I studied a book on Chicago-based ecclesiastical architecture for stained glass palettes. Below is the direction I went in for my church, with solid and definitive black lines functioning as the key plate. The vibrancy of images from a French type specimen also resonated as color existed in this use of metal type in a way that it does not in early Chicago type specimens.

The final form is comprised of individual layers representing buildings, homes and locales in the city. While setting this I developed the second guiding principle of this project. For each of the 10 prints, or ‘elevations,’ there would also be 10 ‘construction drawings.’ Following the memoir theme of building a life that celebrates both the public and ‘pretty’ side alongside the mundane, this would allow me to present supporting information in the form of drafting, a skill I learned in the pre-CAD days. This part of the project, which will offer all the minutiae of my research and form development, will follow the completion of the prints.

After the black was printed, five more colors were added to build out a range of visual texture in the print.

I printed a simple starter prospectus in order to share it with others and forward my internal dialog about what the project would be. There’s a shocking lack of organization going into it; I do not have all of the specs hammered out, don’t know exactly how it will be presented, not quite sure what each print will look like. This is scary for someone whose shop is organized with a precision that satisfies preservation librarians.

That said, when a print begins to take shape it is not unlike giving birth; I struggle to breathe, scream for an epidural, go to war with all of the little metal soldiers and when it is finished, I am exhausted, exhilarated and sad. I did not hit my initial deadline because of the emotional space needed between producing each print.

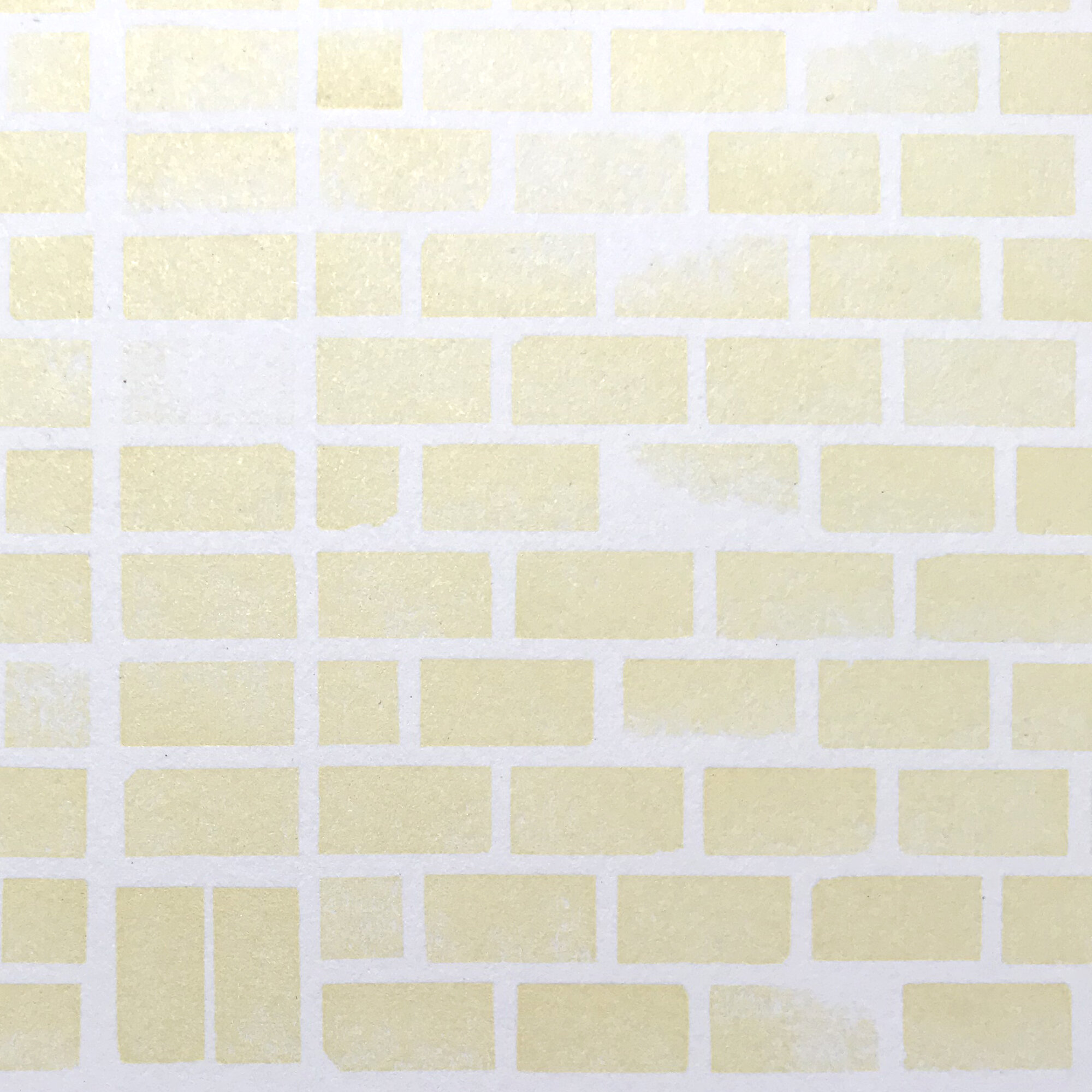

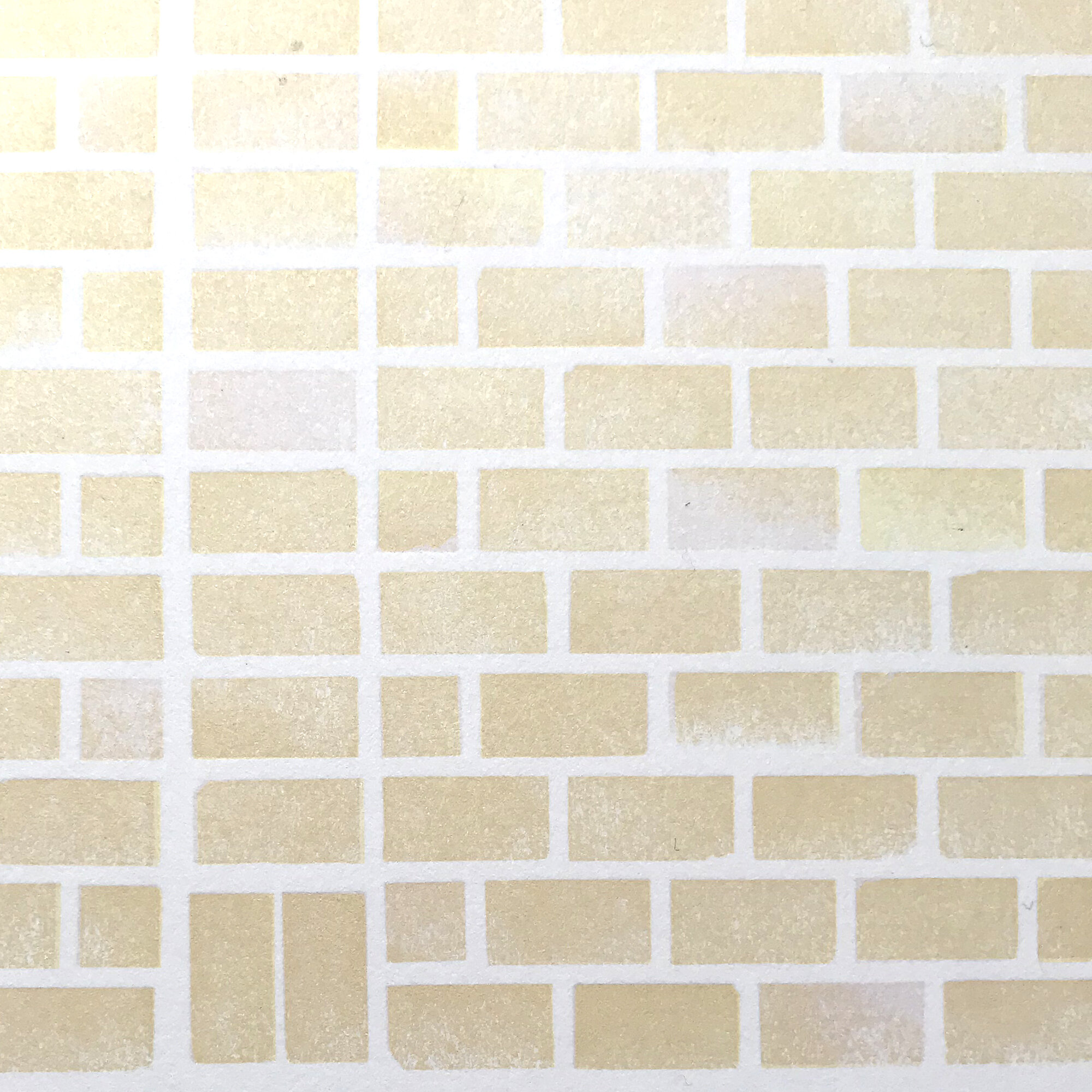

Brick is the foundation of Chicago. In the 1920’s, brick manufacturers were turning our clay into 700 million ‘Chicago Common’ bricks a year. This continued into the 70’s when EPA regulations would drastically alter manufacturing capabilities and the demand decreased. But the ubiquitous brick is everywhere, on the backsides of buildings and as a major component of construction you can’t see. This includes the below exposed bricks at the Newberry during the renovation of the Library’s first floor. These ones were obviously not meant to be seen.

Years ago, there was a city initiative with accompanying signage that said ‘Rebuilding Chicago’ and it was posted at every construction site. For some reason, and I could conjecture over a Chicago Handshake with fellow citizens, these were changed to ‘Building a New Chicago.’ But prior to that change, the original campaign left an imprint on my thought pattern for a print.

I built a brick wall of type high wood scraps to serve as the backdrop for a collection of typefaces that I grouped because they best represented the kinds of handstyles I see scrawled in the alley.

Chicago Commons fired to a range of yellows and pinks that made them unique in the world. To achieve this, I printed my wood bricks in three passes, altering which side of the wood printed and how they were inked.

I kept ‘Rebuilding Chicago’ after the signs disappeared because every time we saw one, Jo would exclaim ‘But I liked it the way it was!’ The irony of this is that my child hit on something key to construction in the city; it is largely focused on the areas of privilege that need it the least. Like our neighborhood.

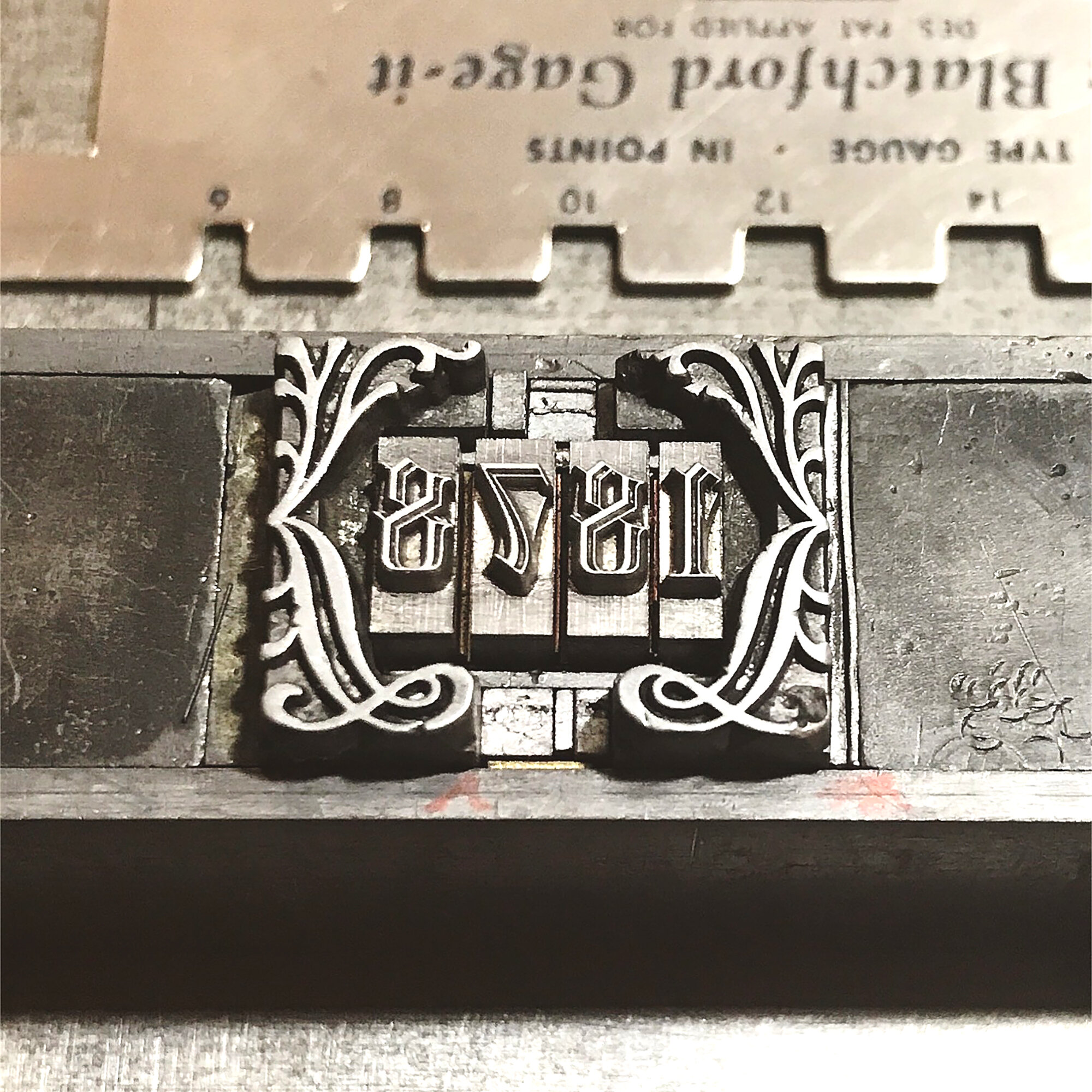

The historical component of this print is the inclusion of clues about the development of the type measuring point system we use today. Chicago’s Marder, Luse & Co. took the lead role in this standardization.

The year mimics the way a cornerstone is engraved with the founding date of a building. And the names previously used to reference type sizes are also included, as they can appear as nonsensical to the uninitiated as graffiti writers’ tags.

As I dive into the final four prints of the series this fall and polish my thoughts and scribbles on the three that are the subject of my next post, I am cautiously optimistic about the direction of the project. The varsity team of printers, binders, thinkers, librarians, children and weirdos I have assembled for support have a shocking capacity for confidence in me to present something that feels representative of my life thus far.

More photos can be seen here and for all the ‘epidural!’ moments, follow me on instagram.

I Have This Thing About Ships

I have this thing about ships. Often the ones that met untimely ends at the bottom of an ocean or through fire. My home library includes accounts of the Andrea Doria, the Lusitania, Walter Lord’s thorough accounts of the Titanic and lists of Great Lakes shipping disasters. Maybe there’s metaphor in it, considering I’ve likened navigating loss, single parenting, health insurance and a small business to steering a ship through icebergs. Maybe it’s my passion for the work of skilled craftspersons who labor for years to create something that carries people from shore to shore, and is then lost in moments. Maybe it’s the beautiful architecture and technology of these vessels that inspires me to be a more thoughtful designer.

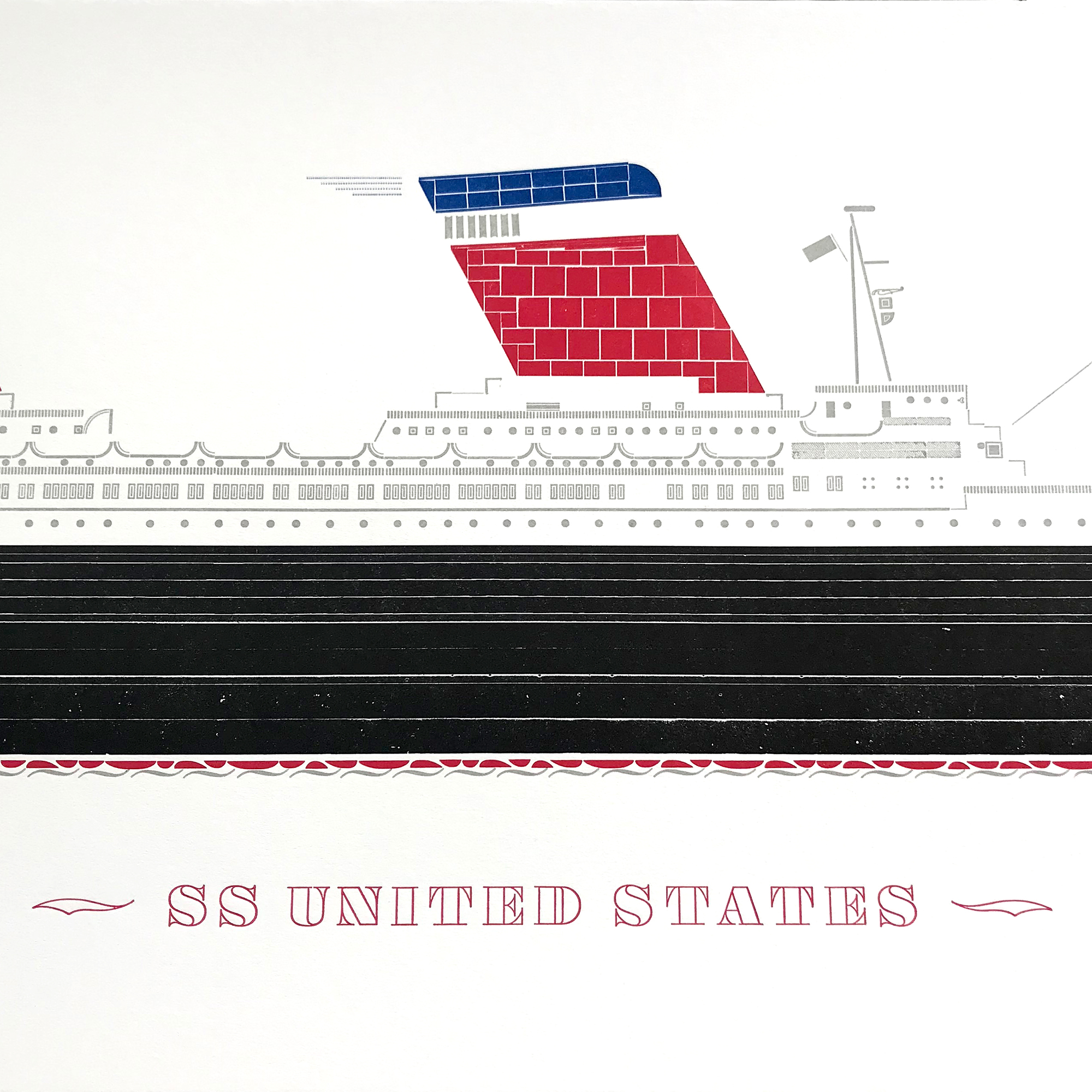

One ship I adore that escaped the fate of those in my library is the SS United States, which made its record-breaking maiden voyage across the Atlantic on July 3rd, 1952. It is a stunning piece of American innovation and her architect, William Gibbs, famously touted her as unsinkable, inflammable and unmatched in speed. By design or circumstance, he was correct.

On May 31st, 1954, my grandmother set sail on the United States, destined for a few weeks with my grandfather, then stationed overseas in the Air Force. Here she is on the stern, in personal photos shared with me.

I’m certain my grandfather’s penchant for ephemera was the impetus for saving the souvenir program and menu from this trip and I couldn’t be happier about it. The incomparable Lester Beall designed these pieces, making them important artifacts for both ship and mid-century design lovers.

One of my own exciting finds is this postcard featuring a beautiful illustration of the ship just prior to her launch. And even better, the card was sent by a representative of Mergenthaler Linotype, whose machine was present to cast lines of type used for shipboard printing. Two of ‘my things’ on one little card!

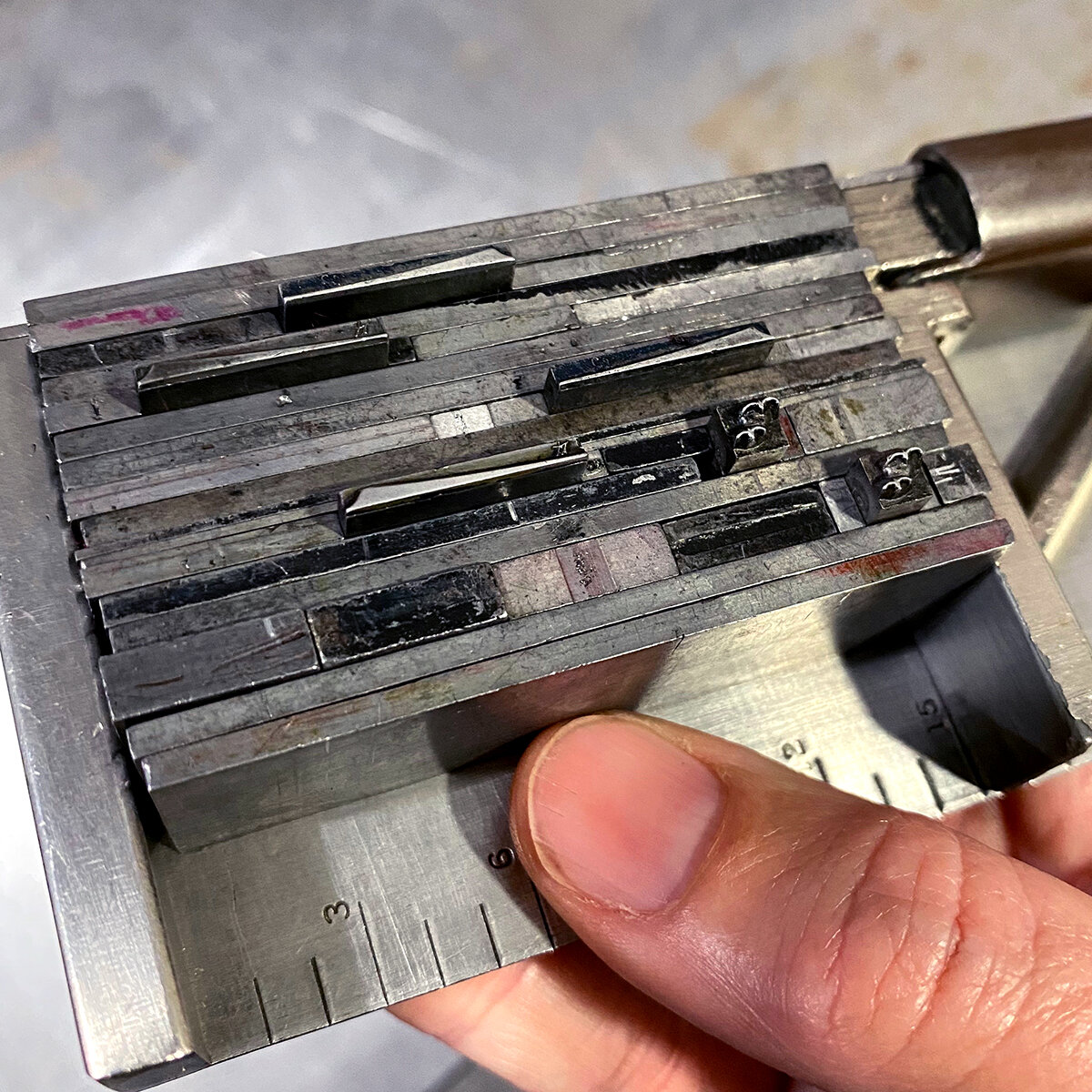

Below is my grandmother’s menu from her first night on the ship as a Cabin Class passenger. This is the kind of thing that would be cast on the Linotype (similar to the slug I am holding at the bottom) and then printed for that day’s meals.

In June I had the honor of being invited to spend a week at John Horn’s Shooting Star Press in Little Rock, Arkansas, alongside other printers I greatly admire. If this is hell, I’d like to spend eternity there.

This sounds snobby, but I’ve spent 20 years building a collection of metal type and ornament and it is extensive and designed for the kind of work I do. It’s rare for me to be in the presence of another collection that inspires me to the level of, or in this case, well beyond, that which I’ve lovingly built. John’s print shop is so well-appointed, well-organized and well-loved that I nearly fell to my knees to praise the printing gods.

These boxes store diverse typefaces that span decades, styles and sizes and I opened every one. John has multiple systems to find, identify and label his collection, making it easy to waltz in with a plan and out with a print.

One section of the shop is purely ornament, with little treasures painstakingly labeled and organized, sometimes even by size and style. These photos represent only a small portion of what is there.

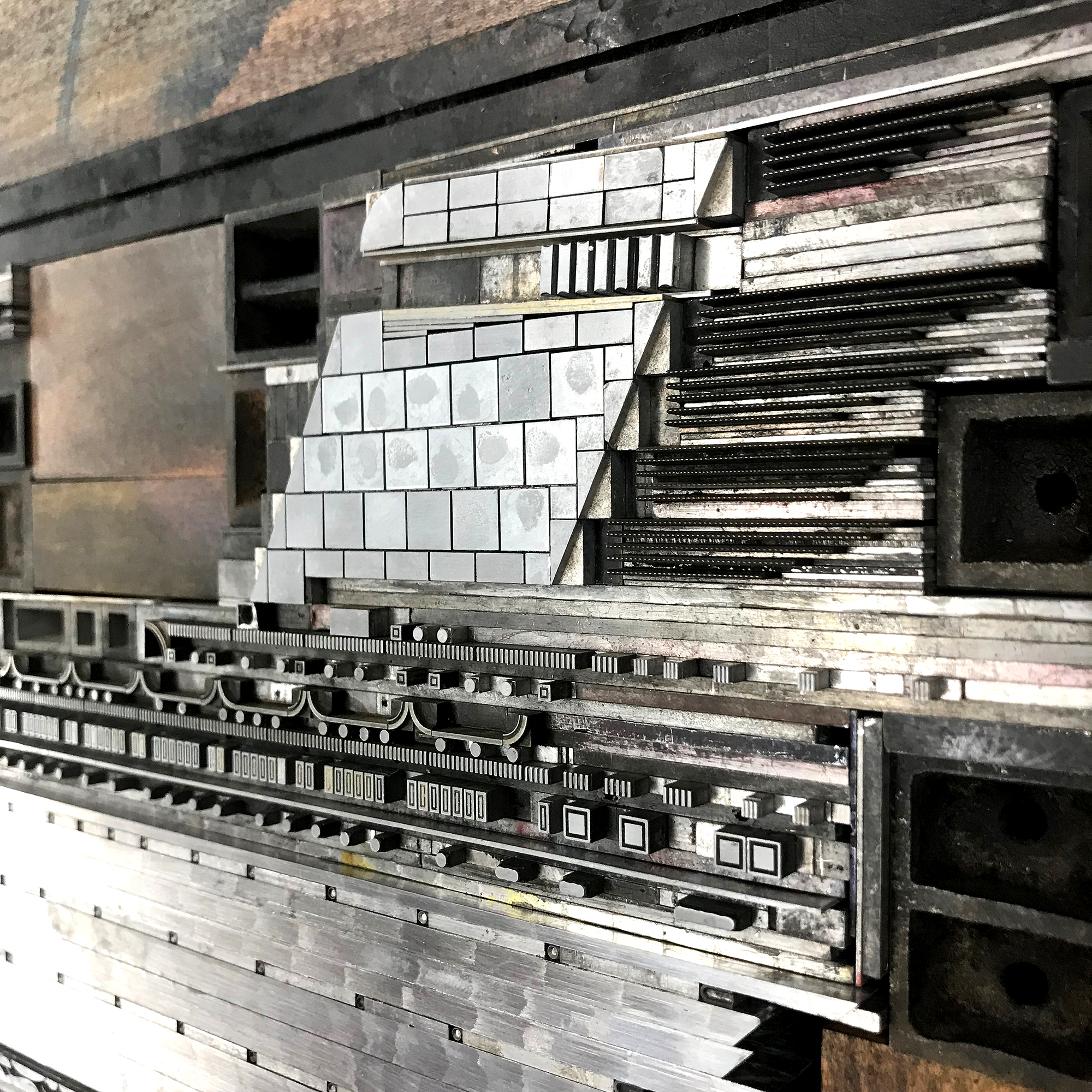

I had it in my head that it might be possible to create a print that would pay homage to the SS United States, in all its streamlined and luxurious glory. And printing at John’s place gave me access to a massive collection of ornaments I don’t have as well as a press that would allow me to print a sheet that’s 25” long. I started sketching potential solutions for the design on my pica paper so that I could easily find ornaments and rule that work with this typographic grid. It didn’t take long to realize the image would be more successful if I didn’t include the entire length of the ship, and instead focused on detail in a loose, illustrative style. The ship is still the fastest cruise ship ever built, so I considered ways to represent her speed.

These images show the slow progression over two days of starting with a letterpress ‘dry dock’ in which I could piece together elements to form the ship.

The distinctive funnels have dotted brass rule trailing behind for ‘speed lines’ and I mitered the ship’s body, made from thick metal rule, and included wave-length ornaments to hint at how it cut through the ocean. While fast, it wasn’t quite fast enough to relieve my poor grandmother from 5 days of seasickness.

My original form included small, 6 point open circles as portholes in what would be the black sides of the ship. These were nearly impossible to print correctly once on press and I scrapped the idea given the limited time I had to work with. I also added more of the wonderful clouds and changed the ornaments framing the name at the bottom to be more in keeping with its style. Major thanks to Jessica Spring for the suggestions on both of these.

Together John and I carried the giant form to the Vandercook Universal III, and here it sits, awaiting its proper lock down for ‘sea trials.’

Usually with multicolored projects, I first pull a proof of the entire form, then mark which colors must be removed to print the first color, then replaced, with the finished color then coming out (repeat for each color.) It’s complicated. But printing this one was not unlike a reduction linoleum cut in that it would be extremely difficult, or impossible, to replace elements once they’d been removed. So I tackled the gray first, as this was the most detailed. Below is how it looked with the red, blue and black removed.

And this is the final print, on Stonehenge white and soft white cotton paper, measuring 25x11”.

The details… I wanted the idea of the ship versus an exact replica and this approach to working with metal type is always the most successful. If I wanted absolute realism, I’d get out the colored pencils instead. So the lifeboats are 1/4 circles in two different weights with a little rule between them. And the funnels are squares, rectangles and rules to fill the solid color area.

Luckily John had the perfect reverse gothic type for the name.

The limited set of prints are now available here. I’m so pleased with the turnout, especially given the time I had. If there was a Blue Riband for typesetting, I would have run away with it.

I’m so grateful for the opportunity to work at Shooting Star Press and it would take another lifetime to fully take advantage of what exists there. John’s unwavering support of my work over the years gave me the confidence to build the ship of my dreams when I wasn’t sure it was a good or even possible idea. It challenged me to look at ornaments in a new way and gave me the scary ‘this could certainly fail BIG’ feeling that pushes me forward.

The SS United States still exists and currently resides in Philadelphia, though the burgeoning airline industry killed her career in the 60s. I can’t bear to post any images of the state she is currently in and her future is not secure. If my print becomes merely a memorial and the familial ephemera just memories, I’ll take that.