I wrote a requiem when I turned 40. It was for a part of myself that bore a nagging, persistent allowance of words that diminished me and the work of my hands, words that always came from men. I could wax on about why they did this but tomes have been written on the subject already; I could address why I tolerated it but this is also well-covered ground.

The only pseudo-apology I’ve received from a man was ‘sorry, I thought you were a boy.’ I think of this whenever I’m put in a position with a man who wants me to demur to his authority or knowledge so that I’m forced to pause before the words ‘sorry’ or ‘apologize’ escape from me. Because more often than not, it’s a power play and my knowledge is just as powerful.

I constantly correct my child on apologizing: If I say ‘do your laundry’ then do your laundry; it doesn’t require an apology for not having done it. It requires saying ‘okay’ and doing it. No offense has been committed. I’m not sending a child into the world apologizing for their very existence.

I see criticisms of women’s work on social media and the woman posting is quick to apologize for whatever the commenter deemed insufficient. I message her to say ‘Don’t apologize for the work you put in the world!’ More often than not, the troll has nothing in their own feed to indicate they have any advanced knowledge of the subject and if they were truly invested in helping, they’d do it directly and privately and not in a humiliating fashion. It’s a power play.

I’ve tried, whenever possible, to collaborate with other women in my field and have had deeply satisfying results on personal and professional levels. Sometimes a friendship goes years in search of a project and other times I cold call a woman I admire to see if there’s a collaboration waiting to happen.

In 2016, I worked with Jessie Reich of Three Ton Bridge Type Foundry, operating out of the Bixler Letterfoundry in Upstate NY, to create two Chicago Collections of metal ornaments based on architectural elements in the city. You can read more about this project here.

And in 2017 I had the pleasure of collaborating with Geri McCormick of Virgin Wood Type, also in NY, to create two sets of wood type ornaments drawn from looser, prairie-style ornament. Read about developing Ida and Lucy here.

Clearly a print in my typographic memoir needed to cover the fact that I was a woman in print, that I worked in letterpress at a time when it was gaining greatly in popularity and transitioning from a male dominated field to a female one. So I collected many of the things men said to me over the years and wrote them down. Some were actually sent in letters and postcards and I kept them but don’t want to give the senders any more space here than they deserve.

It felt important to use all type designed by women for this print. But therein lies the conundrum– there isn’t much, or at least it isn’t specifically documented and credited to women. So I started with my own ornaments mentioned above, arranged in quilt-like patterns as a nod to a traditionally female craft.

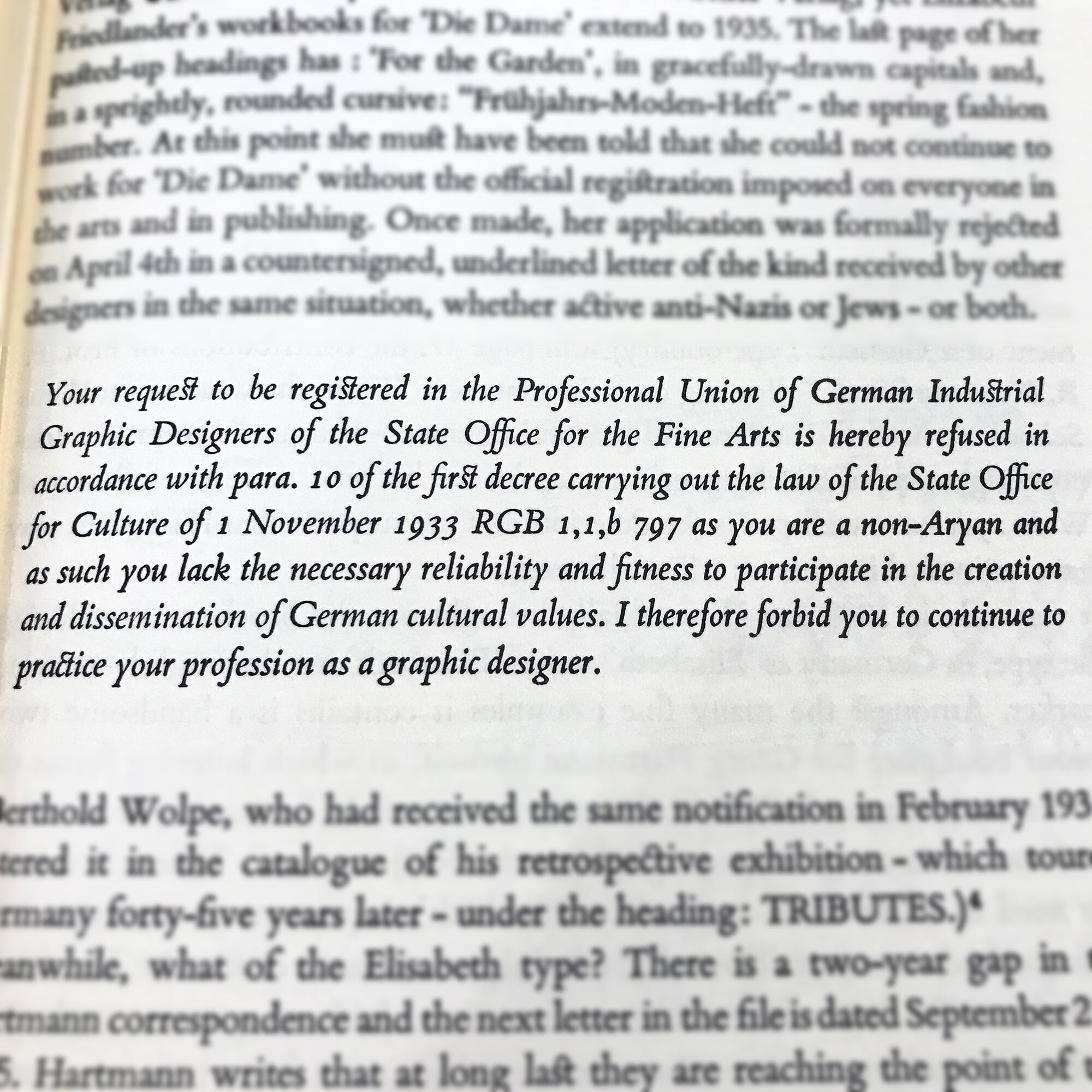

In the winter of 2017 I had the wonderful opportunity to meet Caryl Seidenberg in her home north of Chicago. Moving away from making books, she was selling most of her collection, including a nearly complete run of the typeface Elizabeth, designed by Elizabeth Friedlander. After a delightful morning of looking at her past projects and gleaning what I could from someone who also balanced work and motherhood, I left with all of the Elizabeth type. The Newberry Library has a small archive of materials about Friedlander, including Pauline Paucher’s wonderful book about her life and work. A Jew working in Germany in the late 30s, she was forced to flee to Italy and then England, where she continued to live and work following the war. It’s a story worth reading if you can, even if it requires digging and visiting your special collections library.

I think of the phrase ‘I forbid you to continue to practice your profession’ whenever I’m confronted with sexism because any ‘ism’ is based on the supposition that a perceived flaw prevents one from effectively producing or being something, that your ‘otherness’ is a disability. And after I think about it for a minute, I figure out how to do whatever it was I was told I couldn’t do in a more thoughtful and engaging way to show that I could do it. And this is why anyone marked out as ‘other’ from the ‘norm’ should be listened to; this extra hurdle is where the very seed of innovation is planted.

On May 7th, 2017, my neighbor called me to come home immediately as my house was on fire. By the time I arrived, there were firefighters on the roof, punching holes in it to allow for the release of smoke as the fire itself was out. The rest of the evening was a blur of insurance calls, board ups, neighbors checking in, consoling my child (the electrical fire started in their room and it was a near total loss) and coping with the shock. This image encapsulates so much of that; it shows the layers of my 100 year old home exposed in a near instant.

My little house is a huge source of pride for me. We purchased it in a perfect storm of dumb luck that I never thought would happen: the height of the recession with drastically falling home prices, my husband had steady and rising income from working one job as opposed to several (rare for a stagehand) and Obama’s $8000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers. I had my heart set on one of Chicago’s historic tiny brick bungalows and we got it.

Chicago is well known for its 1871 Great Fire. It took the city about 3 years to rebuild from those damages. It took 9 months to rebuild our home, an excruciating process of constantly calling contractors and cleaning and fighting with utilities and hand-wringing, all while attempting to make life feel normal for a child and running a business. And at the end of May, I dragged my tank of a sewing machine, still reeking of smoke, to Jo’s school to make costumes for the school play. It wasn’t until a while later that Jo realized the irony of being cast as Mrs. O’Leary in a play about Chicago’s history.

And so I built a print to memorialize this time much the way the city was rebuilt on top of sedimentary layers, only my layers were of type dating back to the fire, with my little house resting on top. Then they were printed in earthen, ashen shades.

To add flames, I created a 3-color reduction linoleum cut, printing, then carving away at it multiple times to print depth.

The final print:

I wish I could say the fire experience came with growth, that renovation gave my walls a satisfying symmetry, that I’m relieved our electrical work is up to code. But I can’t. It left a constant, quiet dread, knowing that one day you can leave your home and come back to find it on fire and that you have no control over this. That your definition of ‘home’ and ‘safe’ can vary greatly from your friends and community. That losing a home is like losing a loved one and when someone says ‘but look, you can get a new renovation!’ it’s akin to ‘look, you can get a new child/mother/husband!’ when they die. It wasn’t until the Paradise, California fires when I heard a therapist working with families there express this loss in a way that made me feel understood. That grieving and fear is appropriate. That it’s normal to look at your child when you’re both leaving together and the house is alone by itself, with an unspoken understanding of these feelings.

When our renovation was taking place, its very nature of removing the damage meant removing nearly every bit of handiwork my late husband put into the house and it was like losing him a second time. I was lucky to find a few ‘easter eggs’ in the rubble, including this piece he buried behind drywall in the attic.

These little artifacts are important because they are finite, having lost Mr. S in 2016. He was fiery and passionate about many things, but they largely boiled down to two: his love of his job as a union stagehand coupled with the respect he had for his fellow workers, and his deeply held belief that everyone deserved equality and a start on a level playing field. That meant that if he wasn’t enjoying a cheap beer in our yard, he was at the theater or at a protest rally for whatever underdog needed a loud voice (and he had one). At one of the Newberry Library’s Bughouse Square debates, I watched him heckle Quentin Young while he spoke about the problems of the AMA and the need for single payer health care, something Mr. S actually believed in. Afterwards, he approached Young to shake his hand and say, ‘I believe in everything you said, but I think it’s important to have a lively debate’ and they laughed. If that’s not Chicago, I don’t know what is.

I focused the print about his life on the last few months of it because it was in this time that Mr. S’s long-held beliefs in the strengths and benefits of unions (not always a popular opinion) paid dividends. Over the nine months of his illness, the union showed up in every possible way to support us, thereby validating his lifelong struggle to defend them. Even in the hospital, coming out of anesthesia, he discovered his nurses weren’t in a union and he offered to start one on their behalf.

So I stuck to all the simple, sans serif typefaces, not unlike what we’d see at so many rallies and marches, and organized them into what could either be a sea of posters or the curve of a theatrical proscenium arch. The center pulls specifically from Billy Bragg’s ‘There is Power in a Union.’

Overlapping ornaments point the eye upward, doubling as footlights or poles for the posters.

The shapes of the blocks of text were printed with rough linoleum blocks and then hand inked for a little dimension with this down-and-dirty frisket.

Before Broadway went dark in March, we saw a production of Hadestown, a stunning, modern telling of Orpheus & Eurydice. While we know this is tragedy and long for a different outcome, Hermes is there to emphatically remind us ‘it’s an old tale… it’s a sad song… but we’re going to sing it again.’ The cast follows the performance with an ask for donations to Broadway Cares, an organization founded to help those in the industry fight HIV/AIDS when the rest of the country chose to ignore it, and has grown to help the entire Broadway family when in need. They helped my family in our hour of need. As we left the theater and dropped money in the red bucket, I thought ‘what widow placed money in this bucket five years ago that helped me and my child?’ Hermes was right.

I didn’t write this particular requiem and I can’t change the lyrics. But I, too, will sing it again and again.

This is the second of four posts about The City is my Religion.

Read the first here.